"In Praise of Shakespeare’s Comedies"

Rethinking the best way to introduce Shakespeare to the young

by

John R. MacArthur

January 16th, 2014

Harpers

Like many parents, I’m always looking for an opportunity to pry my kids away from screens and interest them in more edifying entertainment, such as Shakespeare’s plays. My reasons are conventional: I think a widely shared Western “canon” is beneficial to society, no matter how white or how male the writers.

Common cultural language and history are essential to civic harmony, of course, but beyond that it’s reassuring to recognize famous lines of poetry and prose, since it makes you feel part of a larger universe of sentient people. “Oh, I know that line,” is one of the most pleasurable expressions of everyday life. Apart from the authors of the Old Testament, Shakespeare remains the champion of commonly known — and deeply insightful — phrases; his writings provide the surest path to discovering what one might have in common with all sorts of different people.

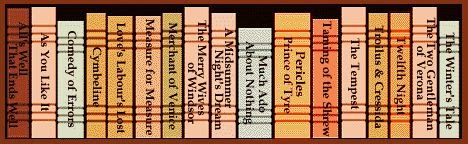

That said, I’m no Shakespeare scholar. I don’t always get the jokes and sardonic asides. Until I bought tickets for the current production of Twelfth Night on Broadway — which spurred me to read some of the text — I didn’t know that “If music be the food of love, play on” begins the play. And I wasn’t aware that the grand-sounding and famous line “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em” is written by rogues to ensnare a foolish character in his own vanity.

I confessed this to my daughters, aged twenty-one and thirteen, so they wouldn’t think me a snob, but also to convince them that anyone can learn something new from a Shakespeare play. I (not my wife) was worried they’d be bored — that following the plot would prove too difficult because of the complicated locutions and Elizabethan language, not to mention Shakespeare’s double entendres and layered irony. But I was wrong. My kids’ attention almost never flagged. Although the story was at times confusing, nobody even hinted that we should go home at intermission.

This version of Twelfth Night, starring Mark Rylance and Stephen Fry, is extraordinary. From the performances, to the costumes, to the highly choreographed curtain call, I don’t think I’ve seen a better theatrical production in the past twenty years.

Having the actors dress for the show in front of the audience is a great idea, but replicating the original atmosphere of the Globe Theatre — with audience members seated in bleachers onstage and an all-male cast that sings and dances — somehow made the play more contemporary and exciting. Still, none of this clever stagecraft would have had much impact if the writing itself weren’t so good, and so funny, which made me rethink my assumptions about the best way to introduce Shakespeare to the young.

I received an excellent, if orthodox, early education in Shakespeare from my high school English teacher, who guided me through the bard’s greatest hits with enthusiasm and aplomb. However, out of respect for traditional pedagogy, he started me on the tragedies and the histories, and we never got to the comedies. My teacher also probably figured that a seventeen-year-old boy would be stimulated by the power struggle and violence of Julius Caesar — the first Shakespeare play I read — and that I would more likely identify with the fun-loving, victorious Prince Hal in Henry IV than I would with, say, the pathetic, self-important Malvolio in Twelfth Night.

My assigned reading in A. C. Bradley’s book Shakespearian Tragedy pushed me further into tragedy’s corner. Perhaps tragic lives were the only theme that really mattered, in drama or in life, since those were tragically violent times: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy assassinated, the Vietnam War raging, and the antiwar movement still occasionally bloody.

But after seeing Twelfth Night I concluded that exposing my neophyte daughters to Richard III or Hamlet or the very frightening Macbeth might have killed their interest in Shakespeare forever. I’m not much animated by sexual politics, but lots of people are these days. The gender confusion, ribald treachery, and coverups in Twelfth Night are surely relevant to teenagers and twentysomethings bombarded with debates about gay marriage, stories of celebrities and politicians brought low by confused sexuality, and the cruelly ironic tilt of so much American comedy. What character better captures the spirit of our mixed-up age than Viola, a female played (in this production) by a male actor, who disguises herself as the page boy Cesario, then is nearly married to Countess Olivia, before being betrothed to Duke Orsino, who has trouble telling Viola apart from her look-alike brother, Sebastian?

With the mystery about who’s who “resolved” at the end of the play, Orsino utters this perfectly logical, but teasingly ambiguous speech to his surprising new fiancée:

Meantime, sweet sister,

We will not part from hence. Cesario, come —

For so you shall be while you are a man,

But when in other habits you are seen,

Orsino’s mistress and his fancy’s queen.

For younger people, overloaded with violent imagery and suffering, I’d hesitate before adding to their burden with the Prince of Denmark’s neurosis or the malevolent rivalries that lead to Romeo and Juliet’s demise. It’s no tragedy to meet Shakespeare for the first time with a smile on your face, and leave the theater laughing.

!["Coupling" 1976 [Gum-bichromate]](http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_IoU3bEFUwWc/S69lnr9G6AI/AAAAAAAAH58/O40Gg-G6rKk/S150/COUPLING+3.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment